"The only thing to fear is fear itself" was stupid advice.

Sure, don't hoard toilet paper – but if policymakers fear fear itself, they'll downplay real dangers to avoid "mass panic". Fear's not the problem, it's how we channel our fear. Fear gives us energy to deal with dangers now, and prepare for dangers later.

Honestly, we (Marcel, epidemiologist + Nicky, art/code) are worried. We bet you are, too! That's why we've channelled our fear into making these playable simulations, so that you can channel your fear into understanding:

- The Last Few Months (epidemiology 101, SEIR model, R & R0)

- The Next Few Months (lockdowns, contact tracing, masks)

- The Next Few Years (loss of immunity? no vaccine?)

This guide (published May 1st, 2020. click this footnote!→1) is meant to give you hope and fear. To beat COVID-19 in a way that also protects our mental & financial health, we need optimism to create plans, and pessimism to create backup plans. As Gladys Bronwyn Stern once said, “The optimist invents the airplane and the pessimist the parachute.”

So, buckle in: we're about to experience some turbulence.

Pilots use flight simulators to learn how not to crash planes.

Epidemiologists use epidemic simulators to learn how not to crash humanity.

So, let's make a very, very simple "epidemic flight simulator"! In this simulation,

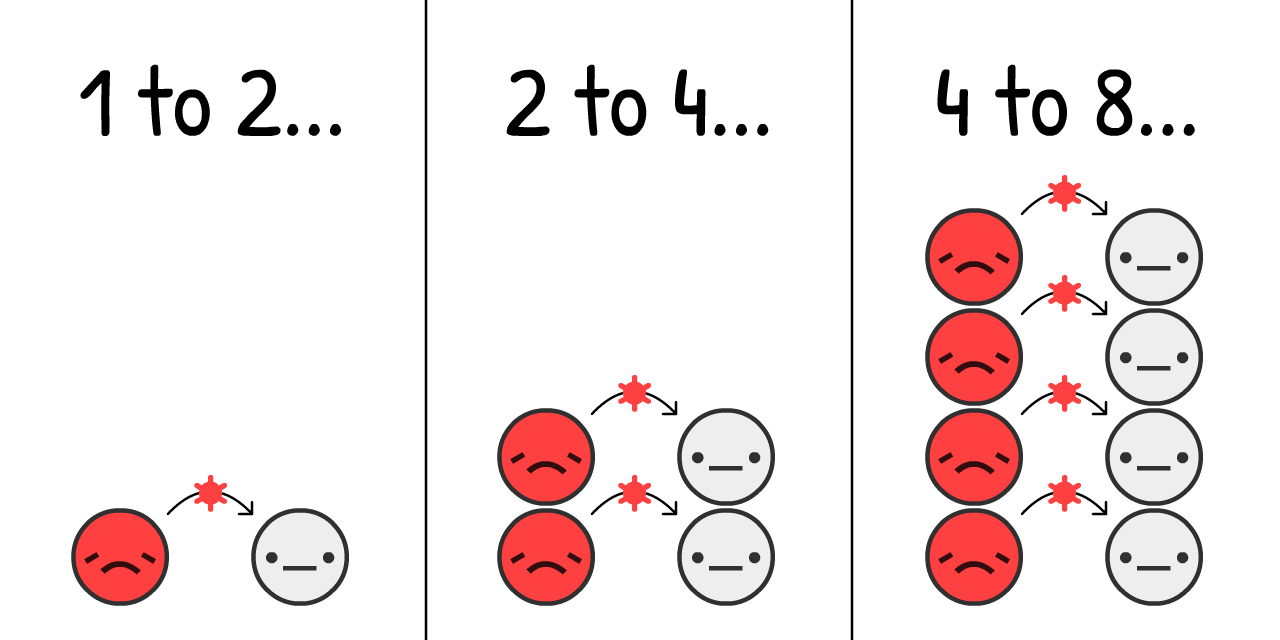

It's estimated that, at the start of a COVID-19 outbreak, the virus jumps from an

If we simulate "double every 4 days" and nothing else, on a population starting with just 0.001%

Click "Start" to play the simulation! You can re-play it later with different settings: (technical caveats: 3)

This is the exponential growth curve. Starts small, then explodes. "Oh it's just a flu" to "Oh right, flus don't create mass graves in rich cities".

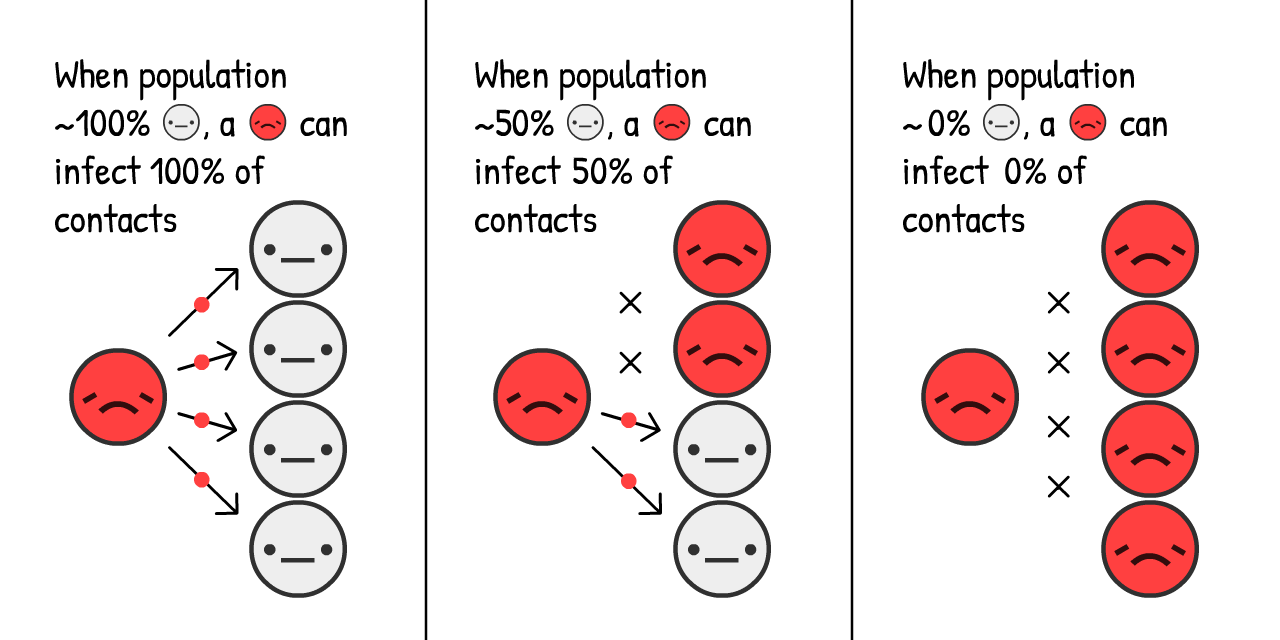

But, this simulation is wrong. Exponential growth, thankfully, can't go on forever. One thing that stops a virus from spreading is if others already have the virus:

The more

How's this change the growth of an epidemic? Let's find out:

This is the "S-shaped" logistic growth curve. Starts small, explodes, then slows down again.

But, this simulation is still wrong. We're missing the fact that

For simplicity's sake, let's pretend that all

With COVID-19, it's estimated you're

This is the opposite of exponential growth, the exponential decay curve.

Now, what happens if you simulate S-shaped logistic growth with recovery?

Let's find out.

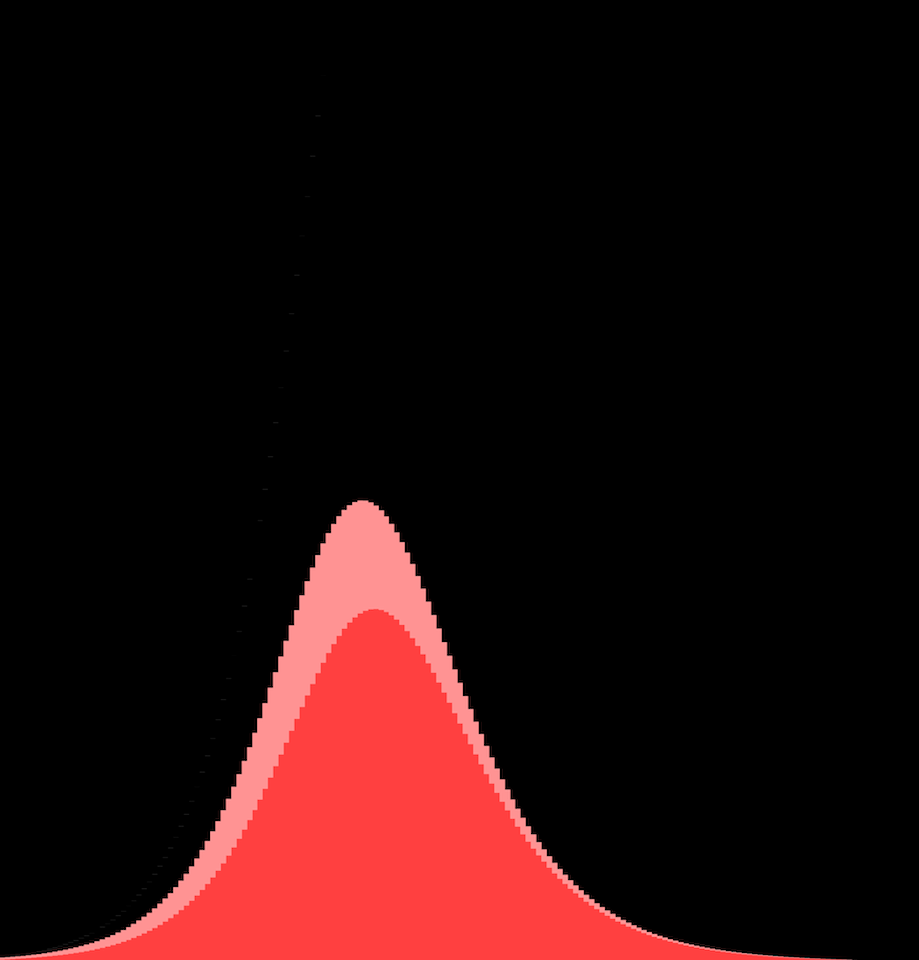

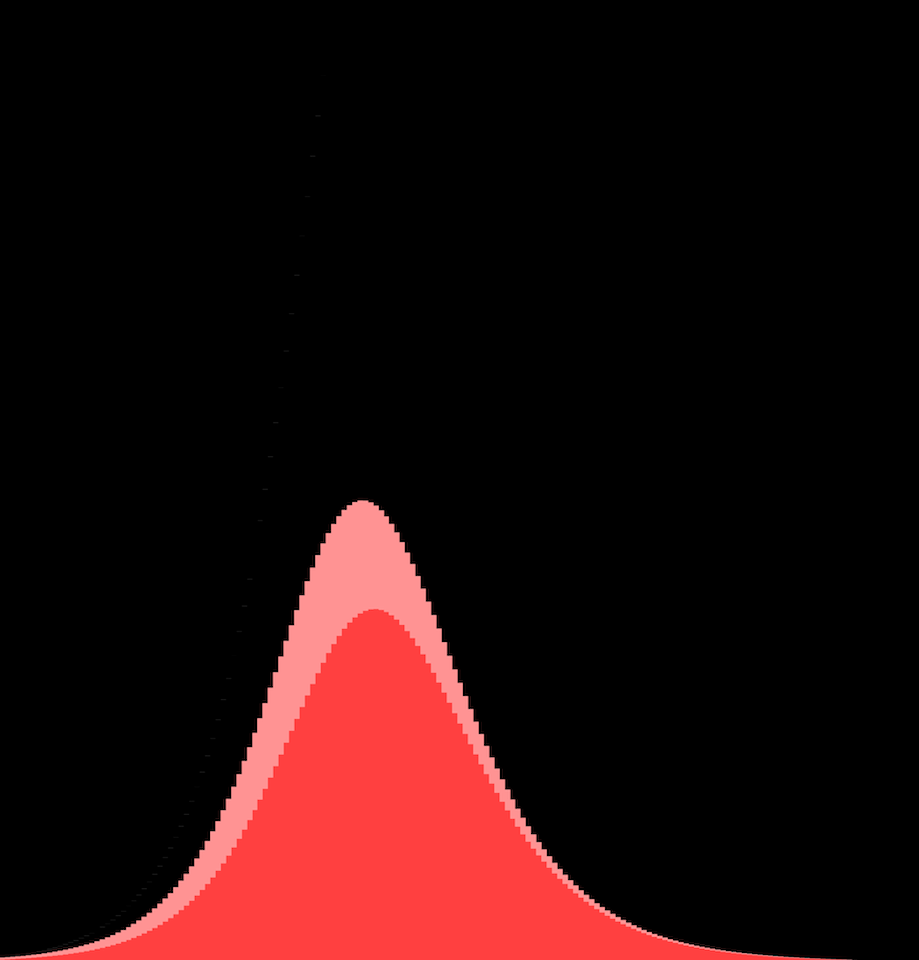

Red curve is current cases

Gray curve is total cases (current + recovered

And that's where that famous curve comes from! It's not a bell curve, it's not even a "log-normal" curve. It has no name. But you've seen it a zillion times, and beseeched to flatten.

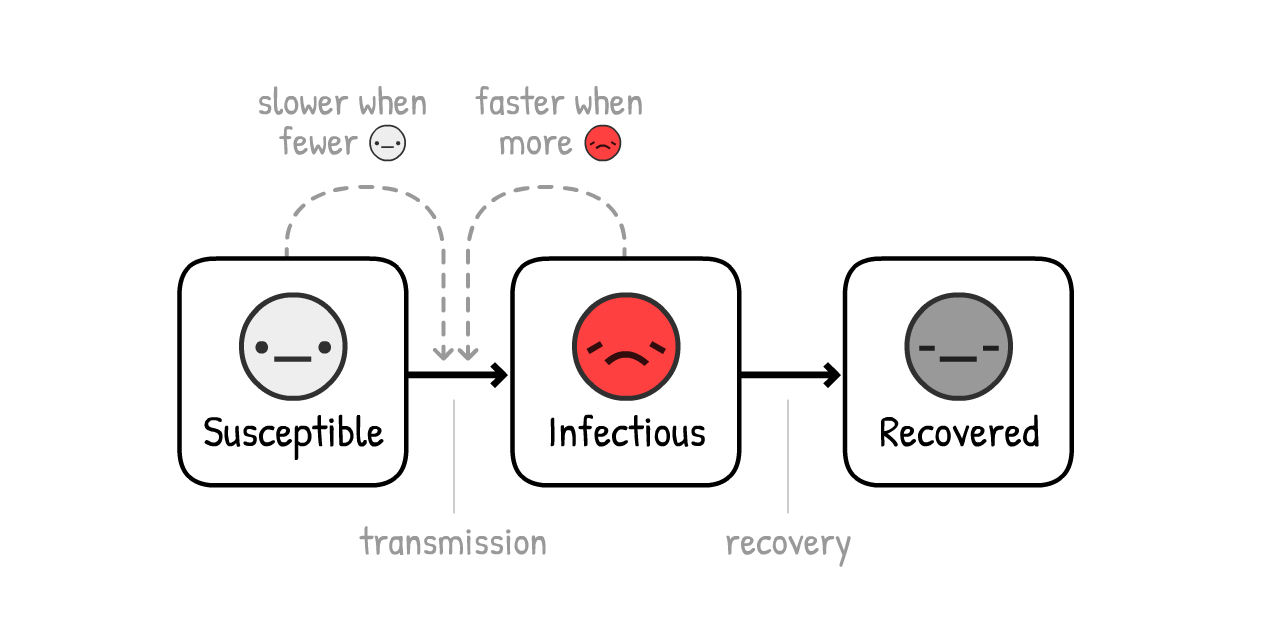

This is the SIR Model,5

(

the second-most important idea in Epidemiology 101:

NOTE: The simulations that inform policy are way, way more sophisticated than this! But the SIR Model can still explain the same general findings, even if missing the nuances.

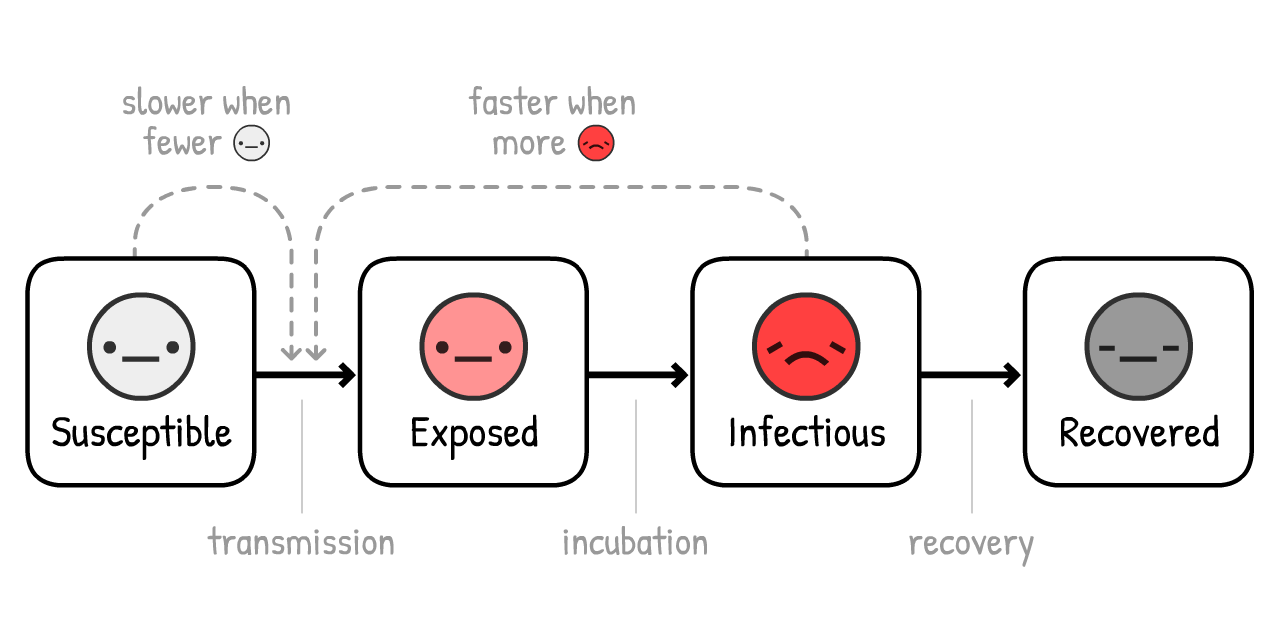

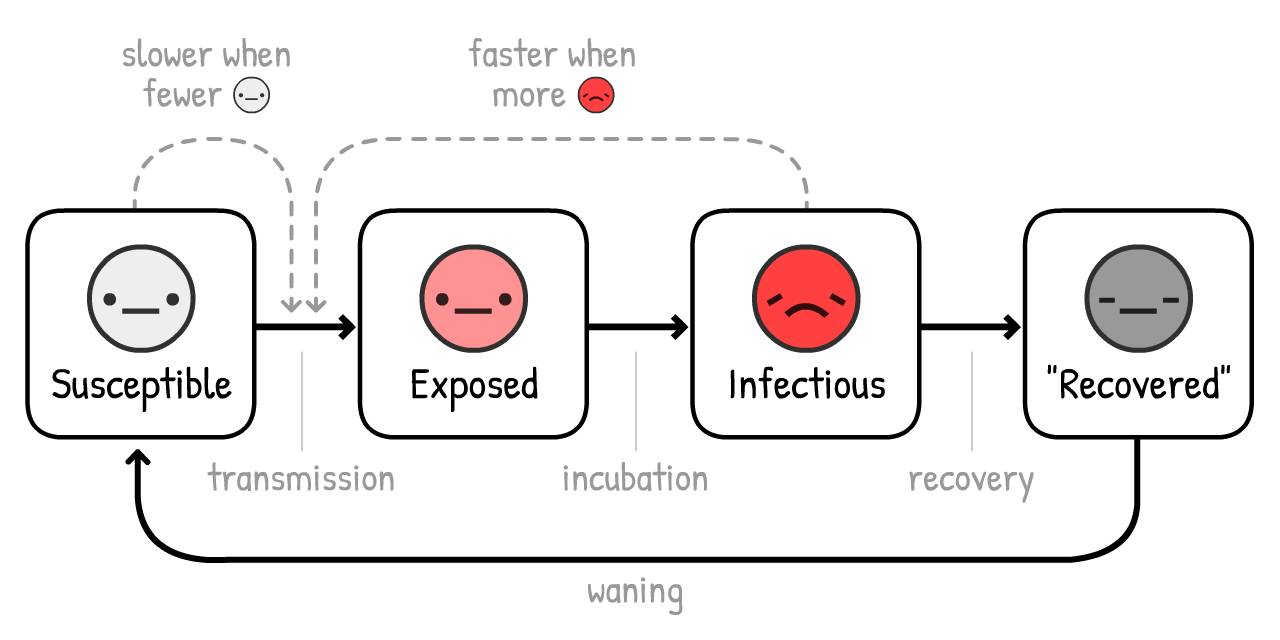

Actually, let's add one more nuance: before an

(This variant is called the SEIR Model6, where the "E" stands for

For COVID-19, it's estimated that you're

Red + Pink curve is current cases (infectious

Gray curve is total cases (current + recovered

Not much changes! How long you stay

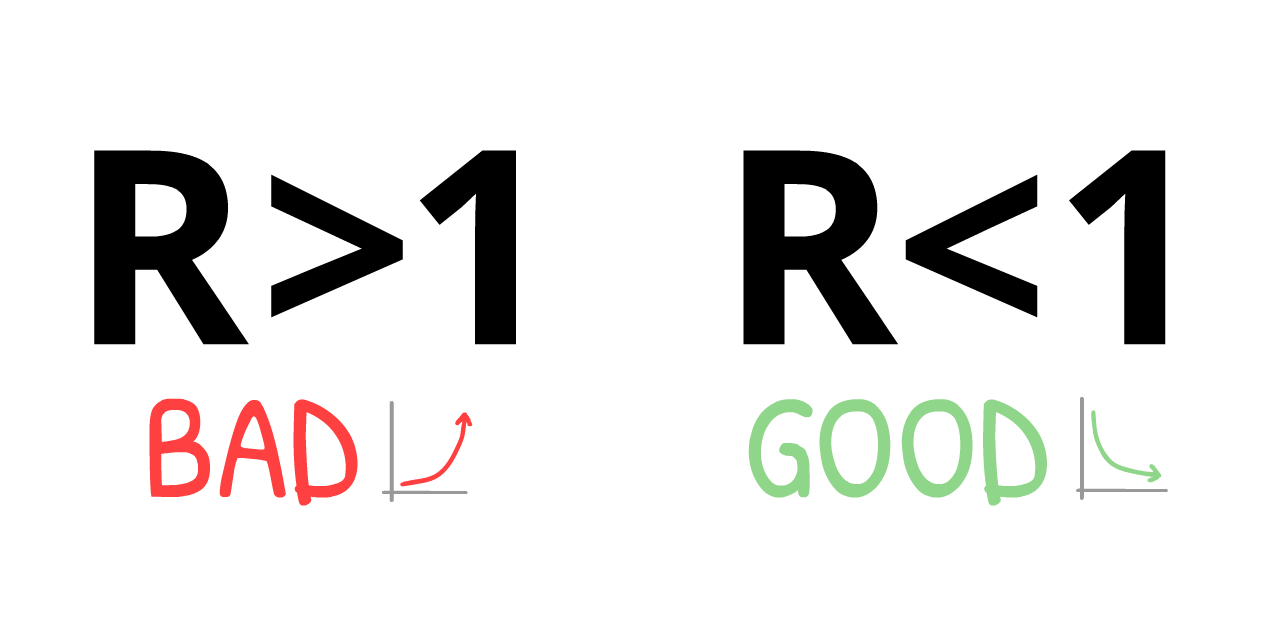

Why's that? Because of the first-most important idea in Epidemiology 101:

Short for "Reproduction number". It's the average number of people an

R changes over the course of an outbreak, as we get more immunity & interventions.

R0 (pronounced R-nought) is what R is at the start of an outbreak, before immunity or interventions. R0 more closely reflects the power of the virus itself, but it still changes from place to place. For example, R0 is higher in dense cities than sparse rural areas.

(Most news articles – and even some research papers! – confuse R and R0. Again, science terminology is bad)

The R0 for "the" seasonal flu is around 1.288. This means, at the start of a flu outbreak, each

The R0 for COVID-19 is estimated to be around 2.2,9 though one not-yet-finalized study estimates it was 5.7(!) in Wuhan.10

In our simulations – at the start & on average – an

Play with this R0 calculator, to see how R0 depends on recovery time & new-infection time:

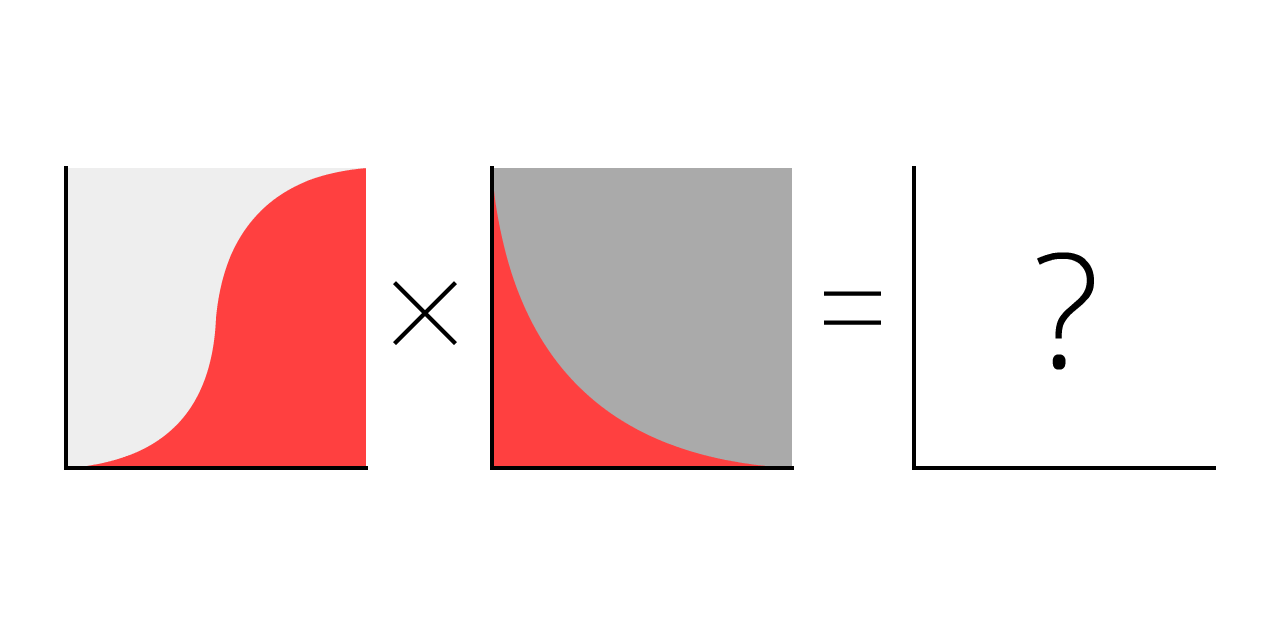

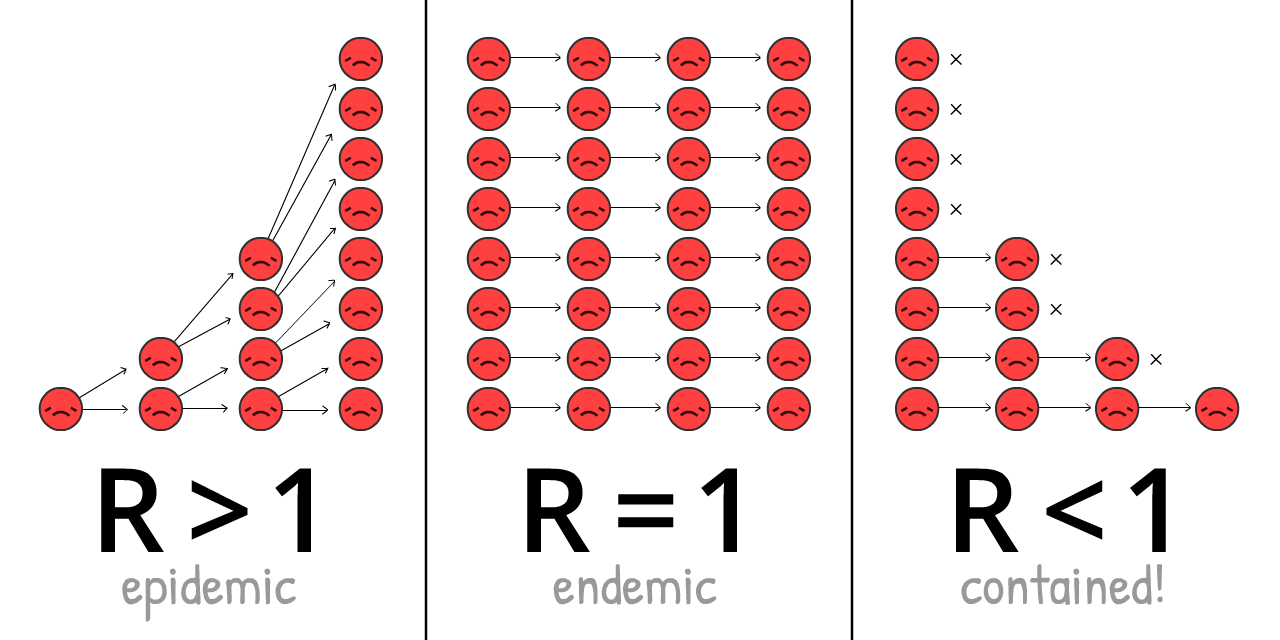

But remember, the fewer

When enough people have immunity, R < 1, and the virus is contained! This is called herd immunity. For flus, herd immunity is achieved with a vaccine. Trying to achieve "natural herd immunity" by letting folks get infected is a terrible idea. (But not for the reason you may think! We'll explain later.)

Now, let's play the SEIR Model again, but showing R0, R over time, and the herd immunity threshold:

NOTE: Total cases does not stop at herd immunity, but overshoots it! And it crosses the threshold exactly when current cases peak. (This happens no matter how you change the settings – try it for yourself!)

This is because when there are more non-

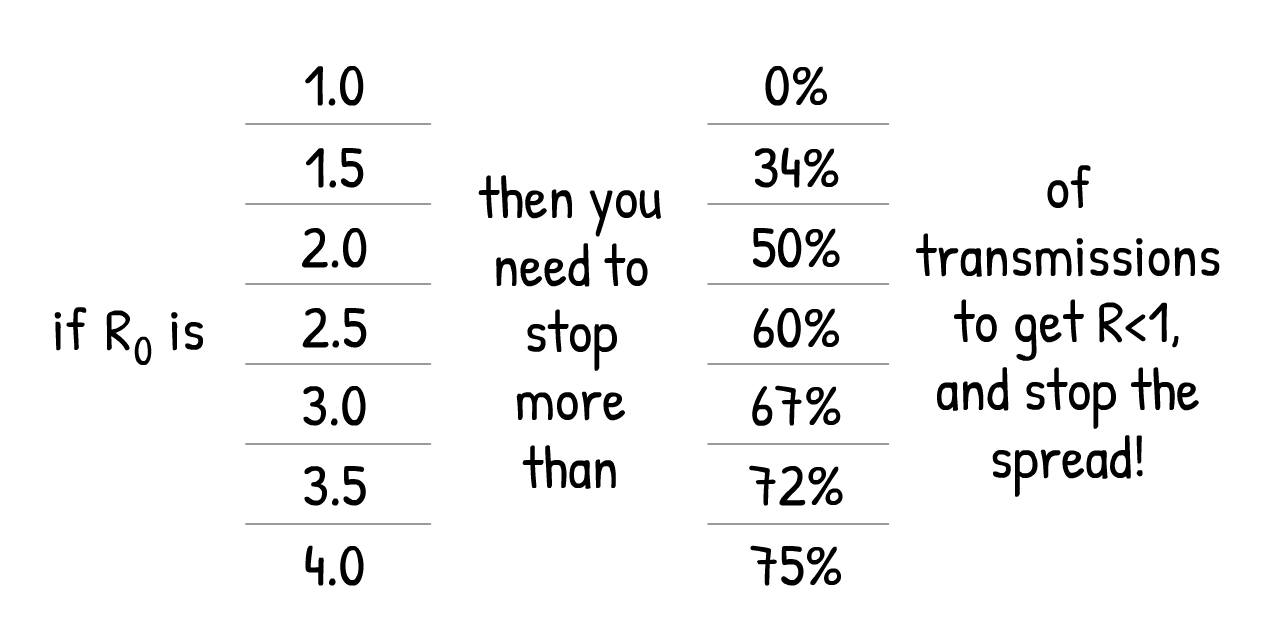

If there's only one lesson you take away from this guide, here it is – it's an extremely complex diagram so please take time to fully absorb it:

This means: we do NOT need to catch all transmissions, or even nearly all transmissions, to stop COVID-19!

It's a paradox. COVID-19 is extremely contagious, yet to contain it, we "only" need to stop more than 60% of infections. 60%?! If that was a school grade, that's a D-. But if R0 = 2.5, cutting that by 61% gives us R = 0.975, which is R < 1, virus is contained! (exact formula:12)

(If you think R0 or the other numbers in our simulations are too low/high, that's good you're challenging our assumptions! There'll be a "Sandbox Mode" at the end of this guide, where you can plug in your own numbers, and simulate what happens.)

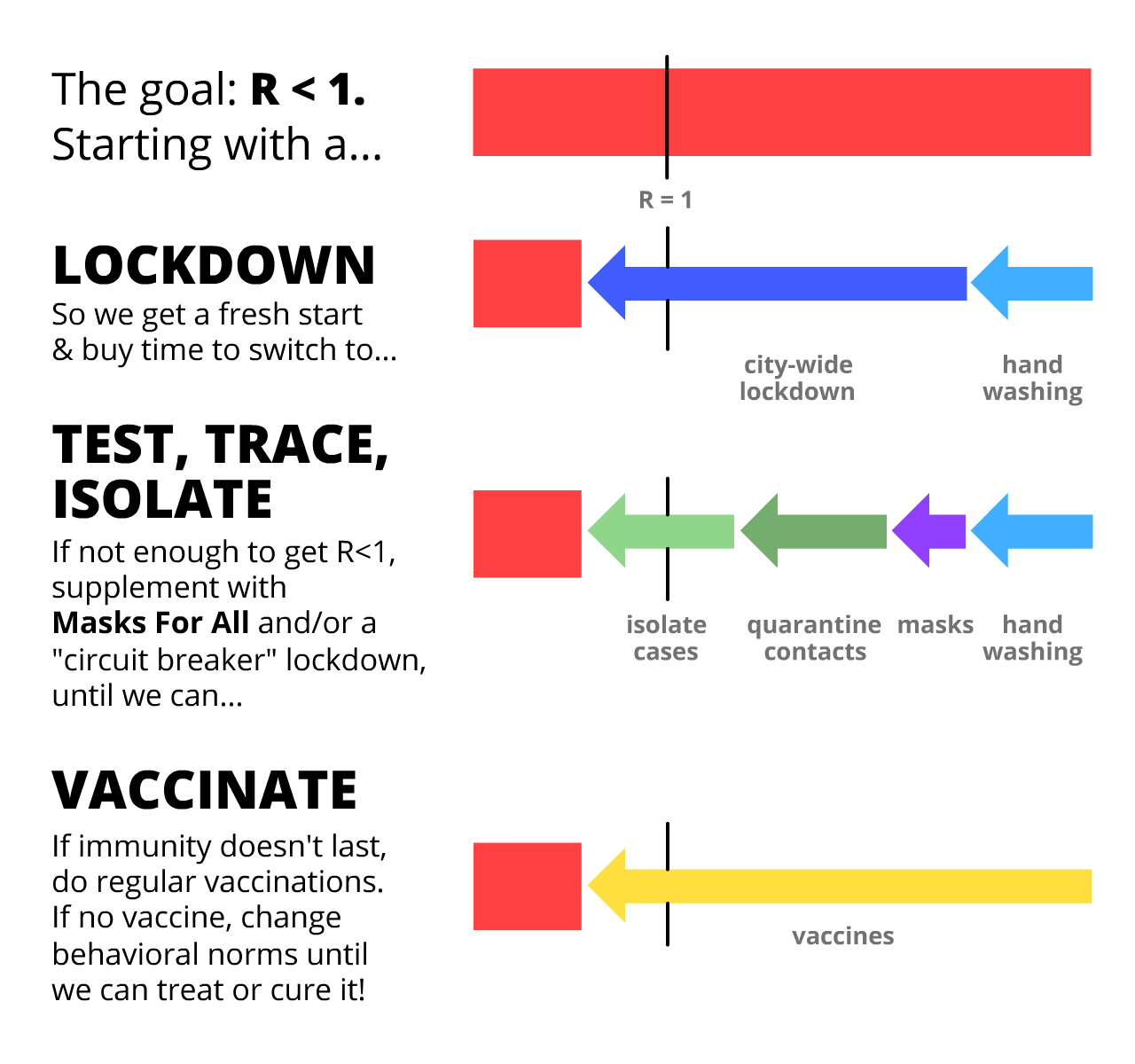

Every COVID-19 intervention you've heard of – handwashing, social/physical distancing, lockdowns, self-isolation, contact tracing & quarantining, face masks, even "herd immunity" – they're all doing the same thing:

Getting R < 1.

So now, let's use our "epidemic flight simulator" to figure this out: How can we get R < 1 in a way that also protects our mental health and financial health?

Brace yourselves for an emergency landing...

...could have been worse. Here's a parallel universe we avoided:

Scenario 0: Do Absolutely Nothing

Roughly 1 in 20 people infected with COVID-19 need to go to an ICU (Intensive Care Unit).13 In a rich country like the USA, there's 1 ICU bed per 3400 people.14 Therefore, the USA can handle 20 out of 3400 people being simultaneously infected – or, 0.6% of the population.

Even if we more than tripled that capacity to 2%, here's what would've happened if we did absolutely nothing:

Not good.

That's what the March 16 Imperial College report found: do nothing, and we run out of ICUs, with more than 80% of the population getting infected. (remember: total cases overshoots herd immunity)

Even if only 0.5% of infected die15 – a generous assumption when there's no more ICUs – in a large country like the US, with 300 million people, 0.5% of 80% of 300 million = still 1.2 million dead... IF we did nothing.

(Lots of news & social media reported "80% will be infected" without "IF WE DO NOTHING". Fear was channelled into clicks, not understanding. Sigh.)

Scenario 1: Flatten The Curve / Herd Immunity

The "Flatten The Curve" plan was touted by every public health organization, while the United Kingdom's original "herd immunity" plan was universally booed. They were the same plan. The UK just communicated theirs poorly.16

Both plans, though, had a literally fatal flaw.

First, let's look at the two main ways to "flatten the curve": handwashing & physical distancing.

Increased handwashing cuts flus & colds in high-income countries by ~25%17, while the city-wide lockdown in London cut close contacts by ~70%18. So, let's assume handwashing can reduce R by up to 25%, and distancing can reduce R by up to 70%:

Play with this calculator to see how % of non-

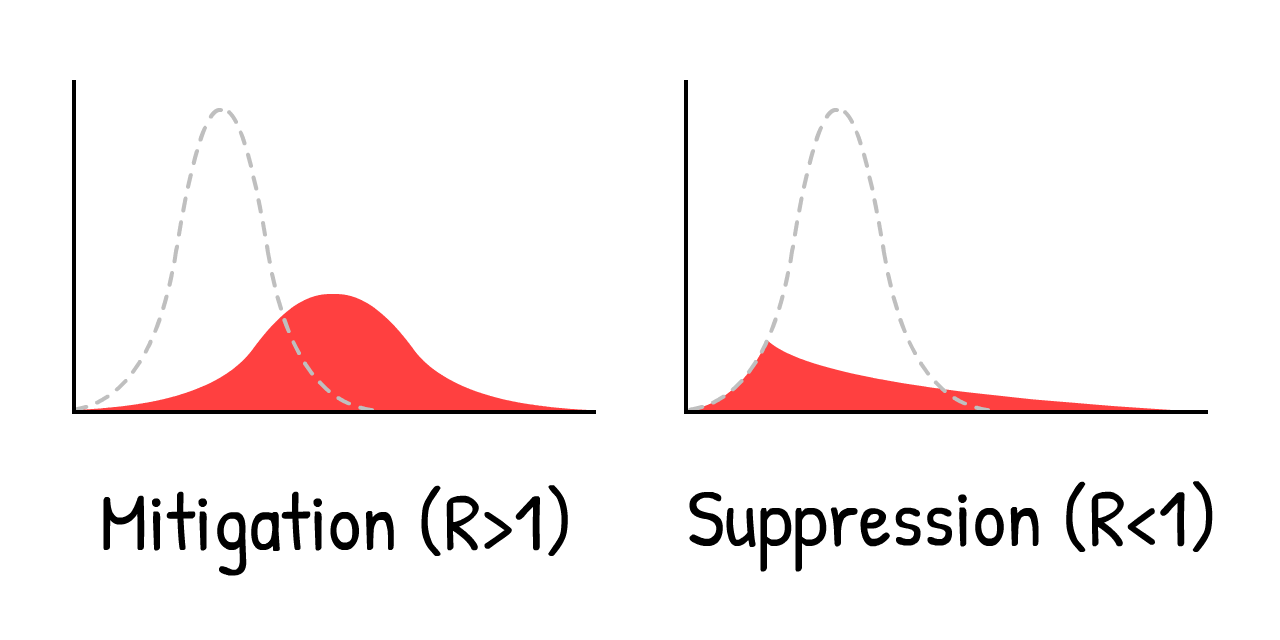

Now, let's simulate what happens to a COVID-19 epidemic if, starting March 2020, we had increased handwashing but only mild physical distancing – so that R is lower, but still above 1:

Three notes:

This reduces total cases! Even if you don't get R < 1, reducing R still saves lives, by reducing the 'overshoot' above herd immunity. Lots of folks think "Flatten The Curve" spreads out cases without reducing the total. This is impossible in any Epidemiology 101 model. But because the news reported "80%+ will be infected" as inevitable, folks thought total cases will be the same no matter what. Sigh.

Due to the extra interventions, current cases peak before herd immunity is reached. In fact, in this simulation, total cases only overshoots a tiny bit above herd immunity – the UK's plan! At that point, R < 1, you can let go of all other interventions, and COVID-19 stays contained! Well, except for one problem...

You still run out of ICUs. For several months. (and remember, we already tripled ICUs for these simulations)

That was the other finding of the March 16 Imperial College report, which convinced the UK to abandon its original plan. Any attempt at mitigation (reduce R, but R > 1) will fail. The only way out is suppression (reduce R so that R < 1).

That is, don't merely "flatten" the curve, crush the curve. For example, with a...

Scenario 2: Months-Long Lockdown

Let's see what happens if we crush the curve with a 5-month lockdown, reduce

Oh.

This is the "second wave" everyone's talking about. As soon as we remove the lockdown, we get R > 1 again. So, a single leftover

A lockdown isn't a cure, it's just a restart.

So, what, do we just lockdown again & again?

Scenario 3: Intermittent Lockdown

This solution was first suggested by the March 16 Imperial College report, and later again by a Harvard paper.20

Here's a simulation: (After playing the "recorded scenario", you can try simulating your own lockdown schedule, by changing the sliders while the simulation is running! Remember you can pause & continue the sim, and change the simulation speed)

This would keep cases below ICU capacity! And it's much better than an 18-month lockdown until a vaccine is available. We just need to... shut down for a few months, open up for a few months, and repeat until a vaccine is available. (And if there's no vaccine, repeat until herd immunity is reached... in 2022.)

Look, it's nice to draw a line saying "ICU capacity", but there's lots of important things we can't simulate here. Like:

Mental Health: Loneliness is one of the biggest risk factors for depression, anxiety, and suicide. And it's as associated with an early death as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.21

Financial Health: "What about the economy" sounds like you care more about dollars than lives, but "the economy" isn't just stocks: it's people's ability to provide food & shelter for their loved ones, to invest in their kids' futures, and enjoy arts, foods, videogames – the stuff that makes life worth living. And besides, poverty itself has horrible impacts on mental and physical health.

Not saying we shouldn't lock down again! We'll look at "circuit breaker" lockdowns later. Still, it's not ideal.

But wait... haven't Taiwan and South Korea already contained COVID-19? For 4 whole months, without long-term lockdowns?

How?

Scenario 4: Test, Trace, Isolate

"Sure, we *could've* done what Taiwan & South Korea did at the start, but it's too late now. We missed the start."

But that's exactly it! “A lockdown isn't a cure, it's just a restart”... and a fresh start is what we need.

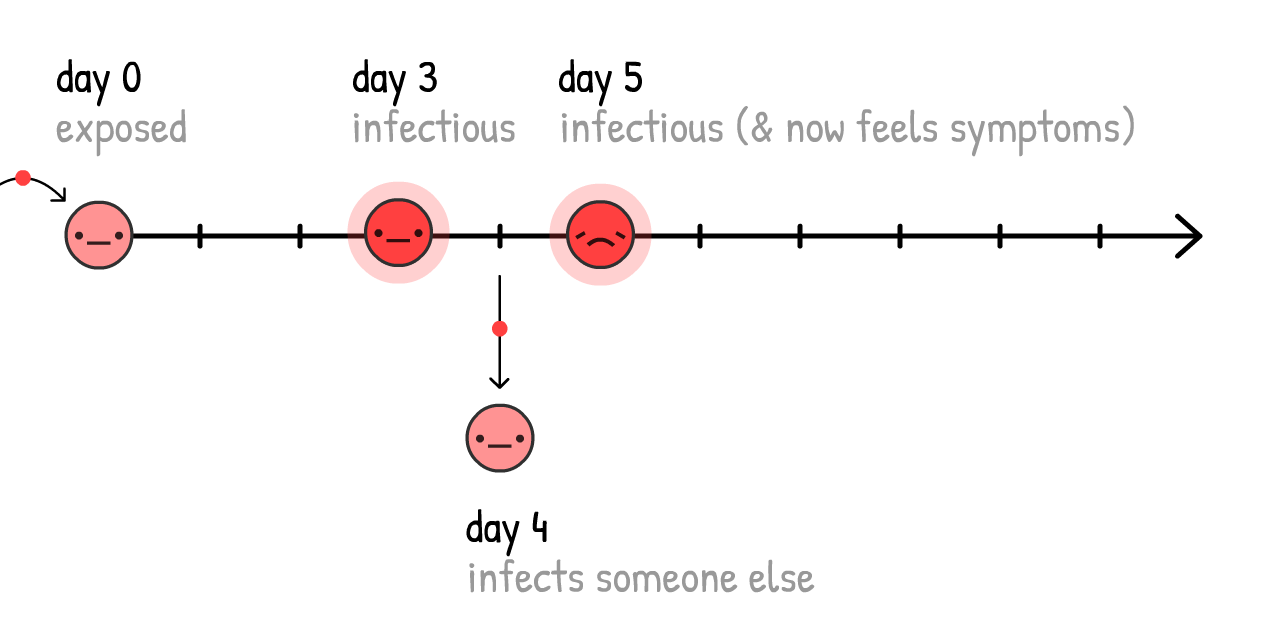

To understand how Taiwan & South Korea contained COVID-19, we need to understand the exact timeline of a typical COVID-19 infection22:

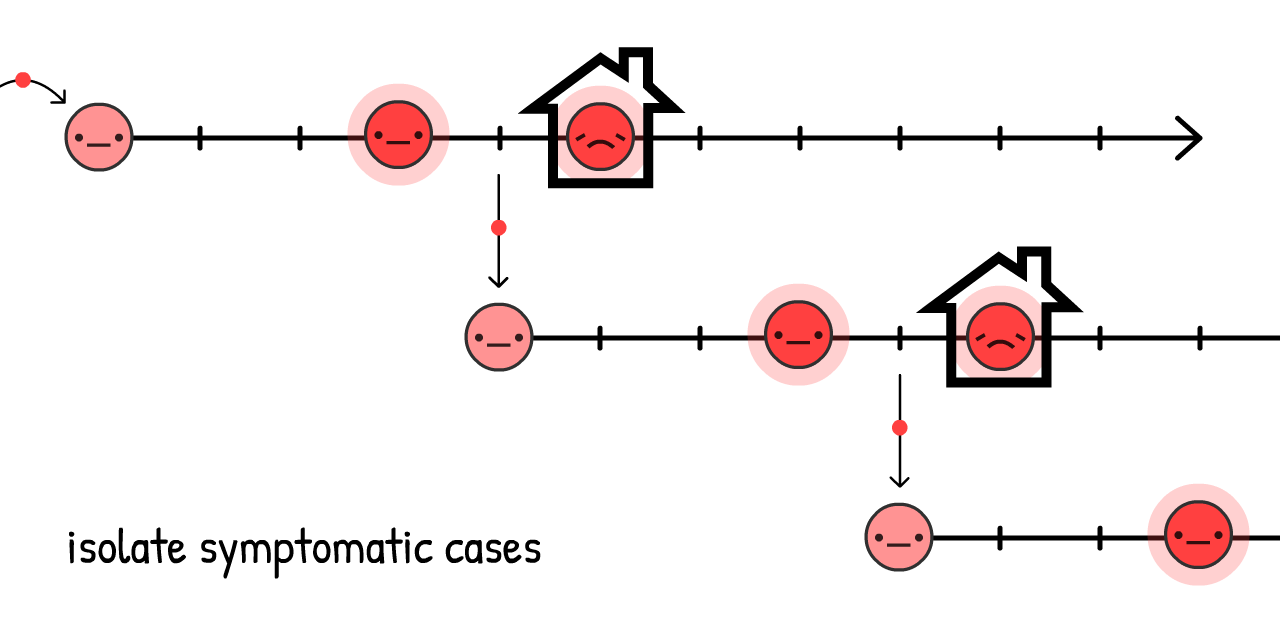

If cases only self-isolate when they know they're sick (that is, they feel symptoms), the virus can still spread:

And in fact, 44% of all transmissions are like this: pre-symptomatic! 23

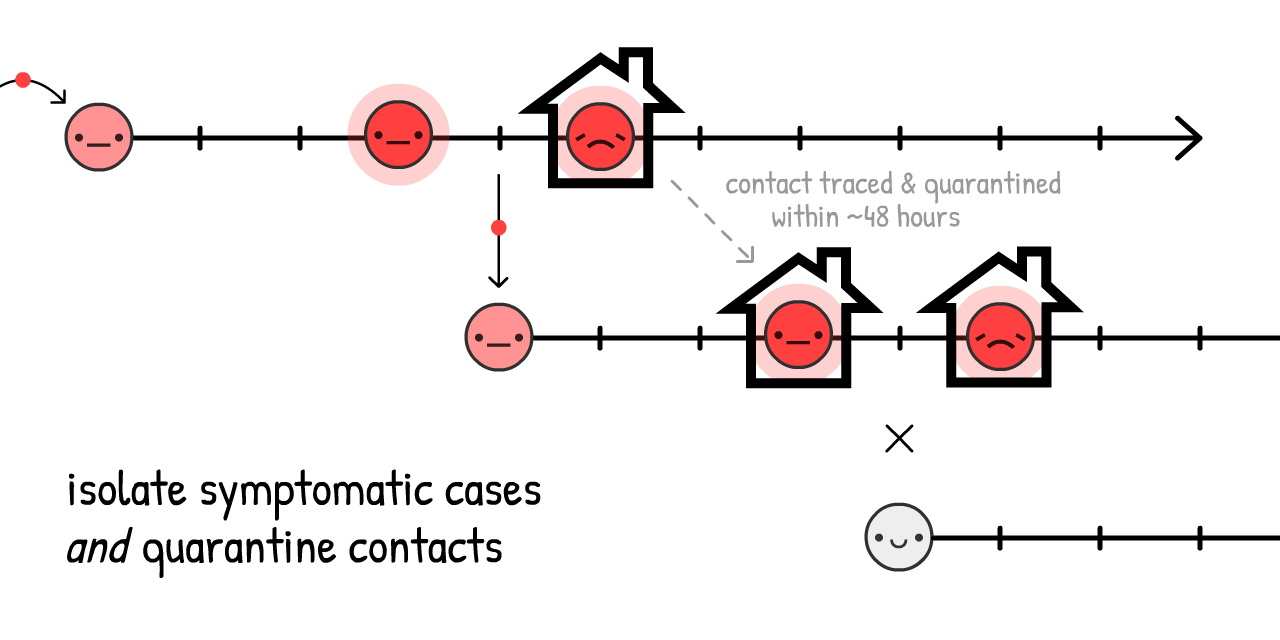

But, if we find and quarantine a symptomatic case's recent close contacts... we stop the spread, by staying one step ahead!

This is called contact tracing. It's an old idea, was used at an unprecedented scale to contain Ebola24, and now it's core part of how Taiwan & South Korea are containing COVID-19!

(It also lets us use our limited tests more efficiently, to find pre-symptomatic

Traditionally, contacts are found with in-person interviews, but those alone are too slow for COVID-19's ~48 hour window. That's why contact tracers need help, and be supported by – NOT replaced by – contact tracing apps.

(This idea didn't come from "techies": using an app to fight COVID-19 was first proposed by a team of Oxford epidemiologists.)

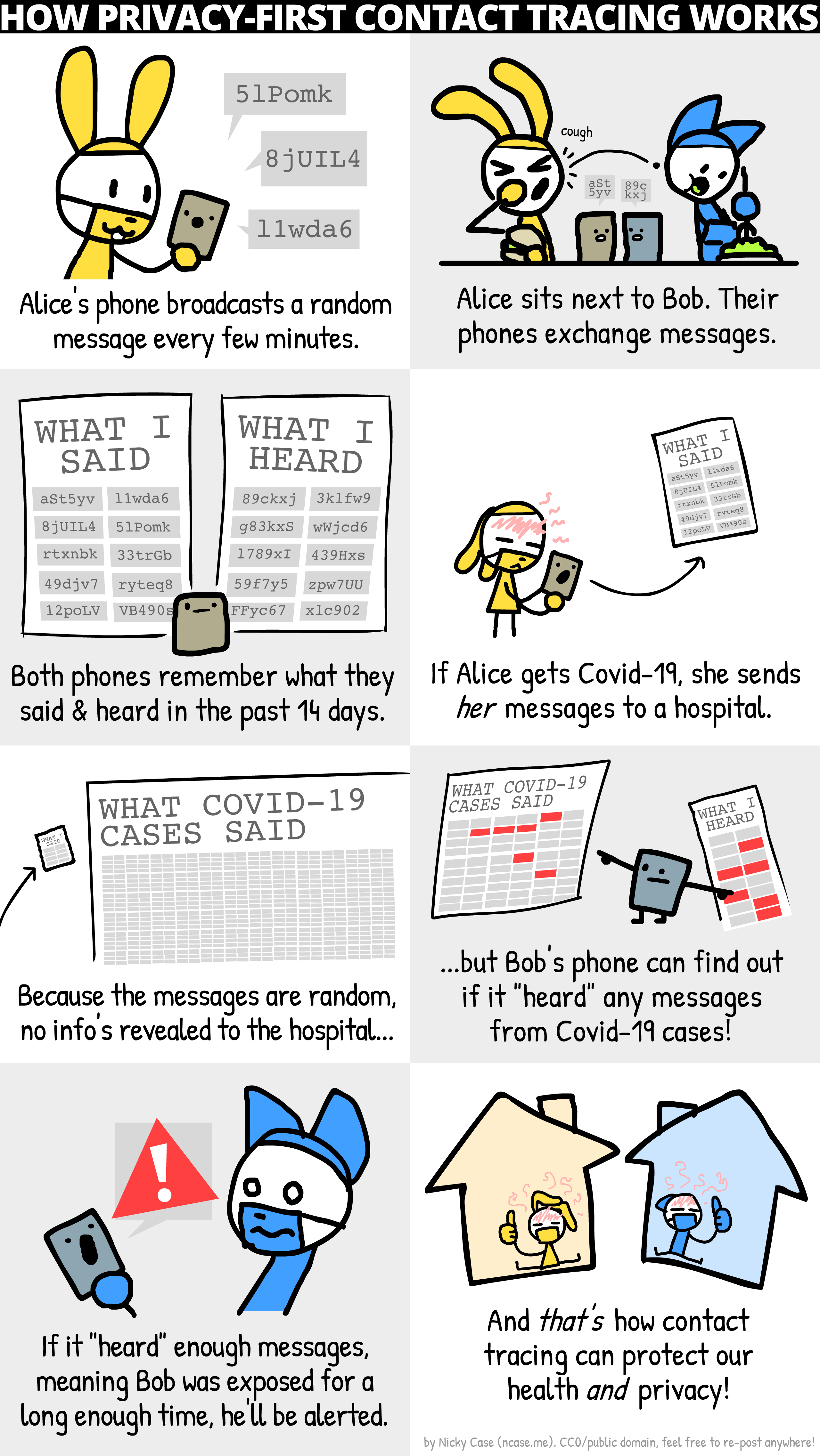

Wait, apps that trace who you've been in contact with?... Does that mean giving up privacy, giving in to Big Brother?

Heck no! DP-3T, a team of epidemiologists & cryptographers (including one of us, Marcel Salathé) is already making a contact tracing app – with code available to the public – that reveals no info about your identity, location, who your contacts are, or even how many contacts you've had.

Here's how it works:

(Here's the full comic. Details about "pranking"/false positives/etc in footnote:25)

Along with similar teams like TCN Protocol26 and MIT PACT27, they've inspired Apple & Google to bake privacy-first contact tracing directly into Android/iOS.28 (Don't trust Google/Apple? Good! The beauty of this system is it doesn't need trust!) Soon, your local public health agency may ask you to download an app. If it's privacy-first with publicly-available code, please do!

But what about folks without smartphones? Or infections through doorknobs? Or "true" asymptomatic cases? Contact tracing apps can't catch all transmissions... and that's okay! We don't need to catch all transmissions, just 60%+ to get R < 1.

(Footnote rant about the confusion between pre-symptomatic vs "true" asymptomatic – "true" asymptomatics are rare:29)

Isolating symptomatic cases would reduce R by up to 40%, and quarantining their pre/a-symptomatic contacts would reduce R by up to 50%30:

Thus, even without 100% contact quarantining, we can get R < 1 without a lockdown! Much better for our mental & financial health. (As for the cost to folks who have to self-isolate/quarantine, governments should support them – pay for the tests, job protection, subsidized paid leave, etc. Still way cheaper than intermittent lockdown.)

We then keep R < 1 until we have a vaccine, which turns susceptible

(Note: this calculator pretends the vaccines are 100% effective. Just remember that in reality, you'd have to compensate by vaccinating more than "herd immunity", to actually get herd immunity)

Okay, enough talk. Here's a simulation of:

- A few-month lockdown, until we can...

- Switch to "Test, Trace, Isolate" until we can...

- Vaccinate enough people, which means...

- We win.

So that's it! That's how we make an emergency landing on this plane.

That's how we beat COVID-19.

...

But what if things still go wrong? Things have gone horribly wrong already. That's fear, and that's good! Fear gives us energy to create backup plans.

The pessimist invents the parachute.

Scenario 4+: Masks For All, Summer, Circuit Breakers

What if R0 is way higher than we thought, and the above interventions, even with mild distancing, still aren't enough to get R < 1?

Remember, even if we can't get R < 1, reducing R still reduces the "overshoot" in total cases, thus saving lives. But still, R < 1 is the ideal, so here's a few other ways to reduce R:

Masks For All:

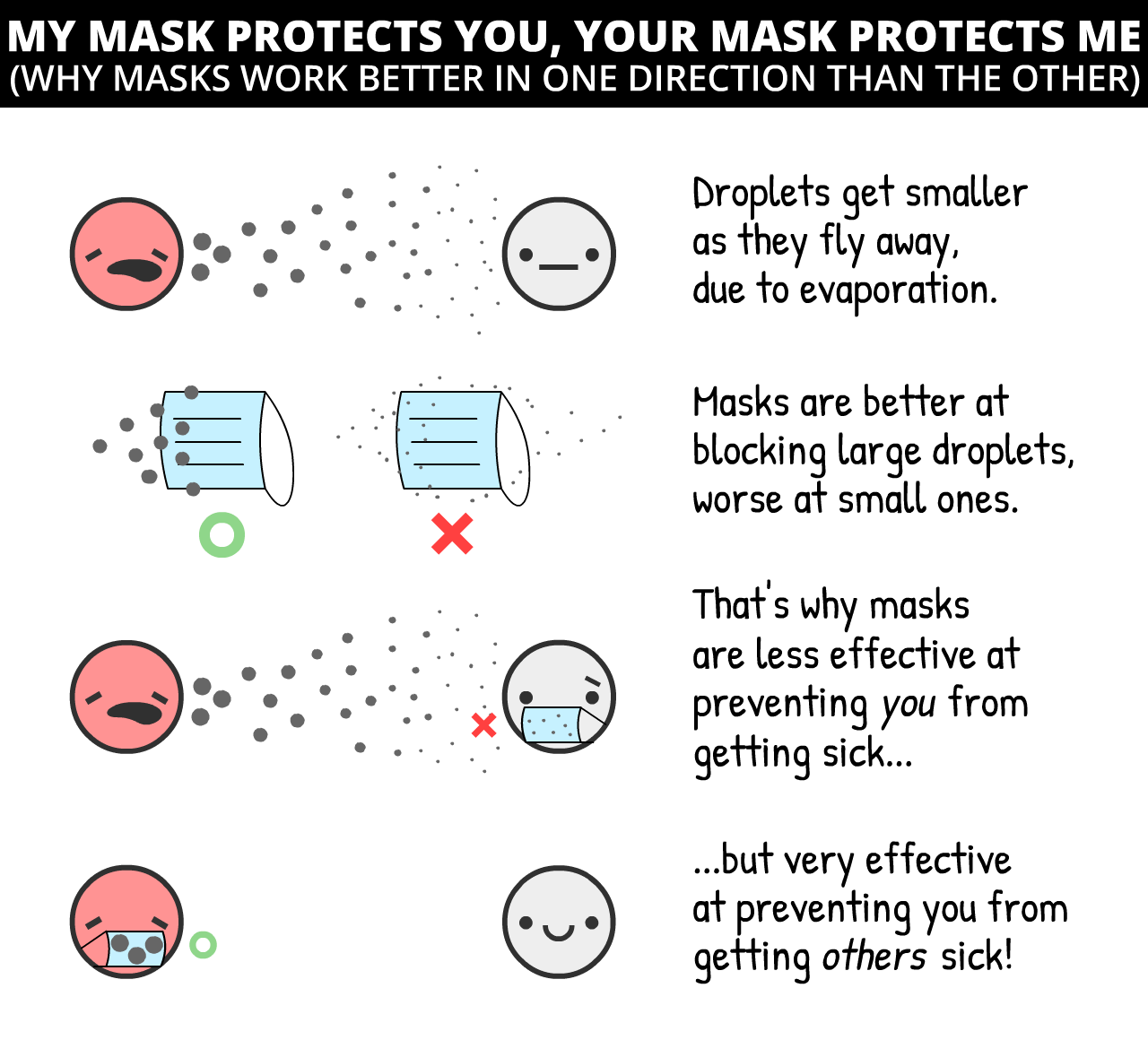

"Wait," you might ask, "I thought face masks don't stop you from getting sick?"

You're right. Masks don't stop you from getting sick31... they stop you from getting others sick.

But wait – how can a simple piece of fabric block droplets in one direction, but not the other? The answer's counter-intuitive, yet simple:

Surgical masks on the infectious person reduce cold & flu viruses in aerosols by 70%32 – that's potentially as large an impact as a lockdown!

However, we don't know for sure the impact of masks on COVID-19 specifically. In science, one should only publish a finding if you're 95% sure of it. (...should.33) Masks, as of May 1st 2020, are less than "95% sure".

However, pandemics are like poker. Make bets only when you're 95% sure, and you'll lose everything at stake. As a recent article on masks in the British Medical Journal notes,34 we have to make cost/benefit analyses under uncertainty. Like so:

Cost: If homemade cloth masks (which are ~2/3 as effective as surgical masks35), super cheap. If surgical masks, more expensive but still pretty cheap.

Benefit: Even if it's a 50–50 chance of surgical masks reducing transmission by 0% or 70%, the average "expected value" is still 35%, same as a half-lockdown! So let's guess-timate that surgical masks reduce R by up to 35%, discounted for our uncertainty. (Again, you can challenge our assumptions by turning the sliders up/down)

(other arguments for/against masks:36)

Masks alone won't get R < 1. But if handwashing & "Test, Trace, Isolate" only gets us to R = 1.10, having just 1/3 of people wear masks would tip that over to R < 1, virus contained!

Summer:

Okay, this isn't an "intervention" we can control, but it will help! Some news outlets report that summer won't do anything to COVID-19. They're half right: summer won't get R < 1, but it will reduce R.

For COVID-19, every extra 1° Celsius (1.8° Fahrenheit) makes R drop by 1.2%.37 The summer-winter difference in New York City is 26°C (47°F),38 so summer will make R drop by ~31%.

Summer alone won't make R < 1, but if we have limited resources, we can scale back some interventions in the summer – so we can scale them higher in the winter.

A "Circuit Breaker" Lockdown:

And if all that still isn't enough to get R < 1... we can do another lockdown.

But we wouldn't have to be 2-months-closed / 1-month-open over & over! Because R is reduced, we'd only need one or two more "circuit breaker" lockdowns before a vaccine is available. (Singapore had to do this recently, "despite" having controlled COVID-19 for 4 months. That's not failure: this is what success takes.)

Here's a simulation of a "lazy case" scenario:

- Lockdown, then

- A moderate amount of hygiene & "Test, Trace, Isolate", with a mild amount of "Masks For All", then...

- One more "circuit breaker" lockdown before a vaccine's found.

Not to mention all the other interventions we could do, to further push R down:

- Travel restrictions/quarantines

- Temperature checks at malls & schools

- Deep-cleaning public spaces

- Replacing hand-shaking with foot-bumping

- And all else human ingenuity shall bring

. . .

We hope these plans give you hope.

Even under a pessimistic scenario, it is possible to beat COVID-19, while protecting our mental and financial health. Use the lockdown as a "reset button", keep R < 1 with case isolation + privacy-protecting contact tracing + at least cloth masks for all... and life can get back to a normal-ish!

Sure, you may have dried-out hands. But you'll get to invite a date out to a comics bookstore! You'll get to go out with friends to watch the latest Hollywood cash-grab. You'll get to people-watch at a library, taking joy in people going about the simple business of being alive.

Even under the worst-case scenario... life perseveres.

So now, let's plan for some worse worst-case scenarios. Water landing, get your life jacket, and please follow the lights to the emergency exits:

You get COVID-19, and recover. Or you get the COVID-19 vaccine. Either way, you're now immune...

...for how long?

- COVID-19 is most closely related to SARS, which gave its survivors 2 years of immunity.39

- The coronaviruses that cause "the" common cold give you 8 months of immunity.40

- There's reports of folks recovering from COVID-19, then testing positive again, but it's unclear if these are false positives.41

- One not-yet-peer-reviewed study on monkeys showed immunity to the COVID-19 coronavirus for at least 28 days.42

But for COVID-19 in humans, as of May 1st 2020, "how long" is the big unknown.

For these simulations, let's say it's 1 year.

Here's a simulation starting with 100%

Return of the exponential decay!

This is the SEIRS Model. The final "S" stands for

Now, let's simulate a COVID-19 outbreak, over 10 years, with no interventions... if immunity only lasts a year:

In previous simulations, we only had one ICU-overwhelming spike. Now, we have several, and

R = 1, it's endemic.

Thankfully, because summer reduces R, it'll make the situation better:

Oh.

Counterintuitively, summer makes the spikes worse and regular! This is because summer reduces new

Thankfully, the solution to this is pretty straightforward – just vaccinate people every fall/winter, like we do with flu shots:

(After playing the recording, try simulating your own vaccination campaigns! Remember you can pause/continue the sim at any time)

But here's the scarier question:

What if there's no vaccine for years? Or ever?

To be clear: this is unlikely. Most epidemiologists expect a vaccine in 1 to 2 years. Sure, there's never been a vaccine for any of the other coronaviruses before, but that's because SARS was eradicated quickly, and "the" common cold wasn't worth the investment.

Still, infectious disease researchers have expressed worries: What if we can't make enough?43 What if we rush it, and it's not safe?44

Even in the nightmare "no-vaccine" scenario, we still have 3 ways out. From most to least terrible:

1) Do intermittent or loose R < 1 interventions, to reach "natural herd immunity". (Warning: this will result in many deaths & damaged lungs. And won't work if immunity doesn't last.)

2) Do the R < 1 interventions forever. Contact tracing & wearing masks just becomes a new norm in the post-COVID-19 world, like how STI tests & wearing condoms became a new norm in the post-HIV world.

3) Do the R < 1 interventions until we develop treatments that make COVID-19 way, way less likely to need critical care. (Which we should be doing anyway!) Reducing ICU use by 10x is the same as increasing our ICU capacity by 10x:

Here's a simulation of no lasting immunity, no vaccine, and not even any interventions – just slowly increasing capacity to survive the long-term spikes:

Even under the worst worst-case scenario... life perseveres.

. . .

Maybe you'd like to challenge our assumptions, and try different R0's or numbers. Or try simulating your own combination of intervention plans!

Here's an (optional) Sandbox Mode, with everything available. (scroll to see all controls) Simulate & play around to your heart's content:

This basic "epidemic flight simulator" has taught us so much. It's let us answer questions about the past few months, next few months, and next few years.

So finally, let's return to...

Plane's sunk. We've scrambled onto the life rafts. It's time to find dry land.45

Teams of epidemiologists and policymakers (left, right, and multi-partisan) have come to a consensus on how to beat COVID-19, while protecting our lives and liberties.

Here's the rough idea, with some (less-consensus) backup plans:

So what does this mean for YOU, right now?

For everyone: Respect the lockdown so we can get out of Phase I asap. Keep washing those hands. Make your own masks. Download a privacy-protecting contact tracing app when those are available next month. Stay healthy, physically & mentally! And write your local policymaker to get off their butt and...

For policymakers: Make laws to support folks who have to self-isolate/quarantine. Hire more manual contact tracers, supported by privacy-protecting contact tracing apps. Direct more funds into the stuff we should be building, like...

For builders: Build tests. Build ventilators. Build personal protective equipment for hospitals. Build tests. Build masks. Build apps. Build antivirals, prophylactics, and other treatments that aren't vaccines. Build vaccines. Build tests. Build tests. Build tests. Build hope.

Don't downplay fear to build up hope. Our fear should team up with our hope, like the inventors of airplanes & parachutes. Preparing for horrible futures is how we create a hopeful future.

The only thing to fear is the idea that the only thing to fear is fear itself.

-

These footnotes will have sources, links, or bonus commentary. Like this commentary! ↩

This guide was published on May 1st, 2020. Many details will become outdated, but we're confident this guide will cover 95% of possible futures, and that Epidemiology 101 will remain forever useful.

(Update May 15: Added citations for "1 in 20 of infected are hospitalized" and "0.5% of infected die")

-

“The mean [serial] interval was 3.96 days (95% CI 3.53–4.39 days)”. Du Z, Xu X, Wu Y, Wang L, Cowling BJ, Ancel Meyers L (Disclaimer: Early release articles are not considered as final versions) ↩

-

Remember: all these simulations are super simplified, for educational purposes. ↩

One simplification: When you tell this simulation "Infect 1 new person every X days", it's actually increasing # of infected by 1/X each day. Same for future settings in these simulations – "Recover every X days" is actually reducing # of infected by 1/X each day.

Those aren't exactly the same, but it's close enough, and for educational purposes it's less opaque than setting the transmission/recovery rates directly.

-

“The median communicable period [...] was 9.5 days.” Hu, Z., Song, C., Xu, C. et al Yes, we know "median" is not the same as "average". For simplified educational purposes, close enough. ↩

-

For more technical explanations of the SIR Model, see the Institute for Disease Modeling and Wikipedia ↩

-

For more technical explanations of the SEIR Model, see the Institute for Disease Modeling and Wikipedia ↩

-

“Assuming an incubation period distribution of mean 5.2 days from a separate study of early COVID-19 cases, we inferred that infectiousness started from 2.3 days (95% CI, 0.8–3.0 days) before symptom onset” (translation: Assuming symptoms start at 5 days, infectiousness starts 2 days before = Infectiousness starts at 3 days) He, X., Lau, E.H.Y., Wu, P. et al. ↩

-

“The median R value for seasonal influenza was 1.28 (IQR: 1.19–1.37)” Biggerstaff, M., Cauchemez, S., Reed, C. et al. ↩

-

“We estimated the basic reproduction number R0 of 2019-nCoV to be around 2.2 (90% high density interval: 1.4–3.8)” Riou J, Althaus CL. ↩

-

“we calculated a median R0 value of 5.7 (95% CI 3.8–8.9)” Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. ↩

-

This is pretending that you're equally infectious all throughout your "infectious period". Again, simplifications for educational purposes. ↩

-

Remember R = R0 * the ratio of transmissions still allowed. Remember also that ratio of transmissions allowed = 1 - ratio of transmissions stopped. ↩

Therefore, to get R < 1, you need to get R0 * TransmissionsAllowed < 1.

Therefore, TransmissionsAllowed < 1/R0

Therefore, 1 - TransmissionsStopped < 1/R0

Therefore, TransmissionsStopped > 1 - 1/R0

Therefore, you need to stop more than 1 - 1/R0 of transmissions to get R < 1 and contain the virus!

-

[UPDATED MAY 15] Many of you rightly pointed out that our previous citation for "1 in 20 need hospitalization" was based off old USA data on confirmed cases – which was way lower than the real number of cases, due to lack of tests. ↩

So, let's look at the country with the most tests per capita: Iceland. On May 15th, 2020, they had 115 hospitalized among 1802 confirmed cases ≈ 6.4% hospitalization rate, or 1 in 16.

A more recent study of COVID-19 in France – using not just official confirmed cases but also antibody test data – found that “3.6% of infected individuals are hospitalized”. Or, 1 in 28.

Overall, there's a lot of uncertainty, but "1 in 20" is roughly close. Besides, for the rest of these simulations, we triple hospital capacity – so, even if "1 in 20" is three times too high, the point still stands.

Old citation:

"Percentage of COVID-19 cases in the United States from February 12 to March 16, 2020 that required intensive care unit (ICU) admission, by age group". Between 4.9% to 11.5% of all COVID-19 cases required ICU. Generously picking the lower range, that's 5% or 1 in 20. Note that this total is specific to the US's age structure, and will be higher in countries with older populations, lower in countries with younger populations. -

“Number of ICU beds = 96,596”. From the Society of Critical Care Medicine USA Population was 328,200,000 in 2019. 96,596 out of 328,200,000 = roughly 1 in 3400. ↩

-

[UPDATED MAY 15] Researchers in Indiana, USA did a random-sample test of the population, and found an infection-fatality rate (IFR) of 0.58%. ↩

-

“He says that the actual goal is the same as that of other countries: flatten the curve by staggering the onset of infections. As a consequence, the nation may achieve herd immunity; it’s a side effect, not an aim. [...] The government’s actual coronavirus action plan, available online, doesn’t mention herd immunity at all.” ↩

-

“All eight eligible studies reported that handwashing lowered risks of respiratory infection, with risk reductions ranging from 6% to 44% [pooled value 24% (95% CI 6–40%)].” We rounded up the pooled value to 25% in these simulations for simplicity. Rabie, T. and Curtis, V. Note: as this meta-analysis points out, the quality of studies for handwashing (at least in high-income countries) are awful. ↩

-

“We found a 73% reduction in the average daily number of contacts observed per participant. This would be sufficient to reduce R0 from a value from 2.6 before the lockdown to 0.62 (0.37 - 0.89) during the lockdown”. We rounded it down to 70% in these simulations for simplicity. Jarvis and Zandvoort et al ↩

-

This distortion would go away if we plotted R on a logarithmic scale... but then we'd have to explain logarithmic scales. ↩

-

“Absent other interventions, a key metric for the success of social distancing is whether critical care capacities are exceeded. To avoid this, prolonged or intermittent social distancing may be necessary into 2022.” Kissler and Tedijanto et al ↩

-

See Figure 6 from Holt-Lunstad & Smith 2010. Of course, big disclaimer that they found a correlation. But unless you want to try randomly assigning people to be lonely for life, observational evidence is all you're gonna get. ↩

-

3 days on average to infectiousness: “Assuming an incubation period distribution of mean 5.2 days from a separate study of early COVID-19 cases, we inferred that infectiousness started from 2.3 days (95% CI, 0.8–3.0 days) before symptom onset” (translation: Assuming symptoms start at 5 days, infectiousness starts 2 days before = Infectiousness starts at 3 days) He, X., Lau, E.H.Y., Wu, P. et al. ↩

4 days on average to infecting someone else: “The mean [serial] interval was 3.96 days (95% CI 3.53–4.39 days)” Du Z, Xu X, Wu Y, Wang L, Cowling BJ, Ancel Meyers L

5 days on average to feeling symptoms: “The median incubation period was estimated to be 5.1 days (95% CI, 4.5 to 5.8 days)” Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, et al

-

“We estimated that 44% (95% confidence interval, 25–69%) of secondary cases were infected during the index cases’ presymptomatic stage” He, X., Lau, E.H.Y., Wu, P. et al ↩

-

“Contact tracing was a critical intervention in Liberia and represented one of the largest contact tracing efforts during an epidemic in history.” Swanson KC, Altare C, Wesseh CS, et al. ↩

-

To prevent "pranking" (people falsely claiming to be infected), the DP-3T Protocol requires that the hospital first give you a One-Time Passcode that lets you upload your messages. ↩

False positives are a problem in both manual & digital contact tracing. Still, we can reduce false positives in 2 ways: 1) By notifying Bobs only if they heard, say, 30+ min worth of messages, not just one message in passing. And 2) If the app does think Bob's been exposed, it can refer Bob to a manual contact tracer, for an in-depth follow-up interview.

For other issues like data bandwidth, source integrity, and other security issues, check out the open-source DP-3T whitepapers!

-

Temporary Contact Numbers, a decentralized, privacy-first contact tracing protocol ↩

-

Apple and Google partner on COVID-19 contact tracing technology . Note they're not making the apps themselves, just creating the systems that will support those apps. ↩

-

Lots of news reports – and honestly, many research papers – did not distinguish between "cases who showed no symptoms when we tested them" (pre-symptomatic) and "cases who showed no symptoms ever" (true asymptomatic). The only way you could tell the difference is by following up with cases later. ↩

Which is what this study did. (Disclaimer: "Early release articles are not considered as final versions.") In a call center in South Korea that had a COVID-19 outbreak, "only 4 (1.9%) remained asymptomatic within 14 days of quarantine, and none of their household contacts acquired secondary infections."

So that means "true asymptomatics" are rare, and catching the disease from a true asymptomatic may be even rarer!

-

From the same Oxford study that first recommended apps to fight COVID-19: Luca Ferretti & Chris Wymant et al See Figure 2. Assuming R0 = 2.0, they found that: ↩

- Symptomatics contribute R = 0.8 (40%)

- Pre-symptomatics contribute R = 0.9 (45%)

- Asymptomatics contribute R = 0.1 (5%, though their model has uncertainty and it could be much lower)

- Environmental stuff like doorknobs contribute R = 0.2 (10%)

And add up the pre- & a-symptomatic contacts (45% + 5%) and you get 50% of R!

-

“None of these surgical masks exhibited adequate filter performance and facial fit characteristics to be considered respiratory protection devices.” Tara Oberg & Lisa M. Brosseau ↩

-

“The overall 3.4 fold reduction [70% reduction] in aerosol copy numbers we observed combined with a nearly complete elimination of large droplet spray demonstrated by Johnson et al. suggests that surgical masks worn by infected persons could have a clinically significant impact on transmission.” Milton DK, Fabian MP, Cowling BJ, Grantham ML, McDevitt JJ ↩

-

Any actual scientist who read that last sentence is probably laugh-crying right now. See: p-hacking, the replication crisis) ↩

-

“It is time to apply the precautionary principle” Trisha Greenhalgh et al [PDF] ↩

-

Davies, A., Thompson, K., Giri, K., Kafatos, G., Walker, J., & Bennett, A See Table 1: a 100% cotton T-shirt has around 2/3 the filtration efficiency as a surgical mask, for the two bacterial aerosols they tested. ↩

-

"We need to save supplies for hospitals." Absolutely agreed. But that's more of an argument for increasing mask production, not rationing. In the meantime, we can make cloth masks. ↩

"They're hard to wear correctly." It's also hard to wash your hands according to the WHO Guidelines – seriously, "Step 3) right palm over left dorsum"?! – but we still recommend handwashing, because imperfect is still better than nothing.

"It'll make people more reckless with handwashing & social distancing." Sure, and safety belts make people ignore stop signs, and flossing makes people eat rocks. But seriously, we'd argue the opposite: masks are a constant physical reminder to be careful – and in East Asia, masks are also a symbol of solidarity!

-

“One-degree Celsius increase in temperature [...] lower[s] R by 0.0225” and “The average R-value of these 100 cities is 1.83”. 0.0225 ÷ 1.83 = ~1.2%. Wang, Jingyuan and Tang, Ke and Feng, Kai and Lv, Weifeng ↩

-

In 2019 at Central Park, hottest month (July) was 79.6°F, coldest month (Jan) was 32.5°F. Difference is 47.1°F, or ~26°C. PDF from Weather.gov ↩

-

“SARS-specific antibodies were maintained for an average of 2 years [...] Thus, SARS patients might be susceptible to reinfection ≥3 years after initial exposure.” Wu LP, Wang NC, Chang YH, et al. "Sadly" we'll never know how long SARS immunity would have really lasted, since we eradicated it so quickly. ↩

-

“We found no significant difference between the probability of testing positive at least once and the probability of a recurrence for the beta-coronaviruses HKU1 and OC43 at 34 weeks after enrollment/first infection.” Marta Galanti & Jeffrey Shaman (PDF) ↩

-

“Once a person fights off a virus, viral particles tend to linger for some time. These cannot cause infections, but they can trigger a positive test.” from STAT News by Andrew Joseph ↩

-

From Bao et al. Disclaimer: This article is a preprint and has not been certified by peer review (yet). Also, to emphasize: they only tested re-infection 28 days later. ↩

-

“If a coronavirus vaccine arrives, can the world make enough?” by Roxanne Khamsi, on Nature ↩

-

“Don’t rush to deploy COVID-19 vaccines and drugs without sufficient safety guarantees” by Shibo Jiang, on Nature ↩

-

Dry land metaphor from Marc Lipsitch & Yonatan Grad, on STAT News ↩

PUBLIC DOMAIN

That means you already have permission to re-use & remix

any of the art/code/words on this page – on blogs, news sites, classrooms, anywhere!

PUBLIC DOMAIN

That means you already have permission to re-use & remix

any of the art/code/words on this page – on blogs, news sites, classrooms, anywhere!